I take a lift into town in the morning after a fourteen-hour sleep. At the ‘taxi rank’ , several minivans await to be full and cruise out to every corner in the country. Unlike Nairobi, some order is seen and minivans are deemed full when the fourteen seats are occupied, with no extra crowding.

‘It is morning time and already steamy hot. We hit a bump and a flat tyre. Our driver has a spare wheel but the jack does not work. I look around and see where Uganda blossoms: ‘He is doing the best he can’ passengers mouth, as they help the driver with the repair. A second minivan stops and lends us a new jack. The two minivans depart at the same time and the rest of the journey to Kampala is of laughs and food sharing. There are no grins, no disdain. Just a bunch of people helping one another.’

Potholed like Swiss cheese, the road winds through hills of tea and coffee plantations and enter villages in flamboyant noise. Lorries cruise next to bicycles and stop for snacks by the roadside. The hills fuse into villages of paved roads and tall lamp posts, privileges of few in this country. The roads collide with each other and gradually fill with more traffic, turning into madness, the sort of madness only Kampala can offer.

Agoraphobics abstain, for Kampala is all about crowds. Its compact city centre encompasses two gigantic taxi parks -call it minivan stations- and two big markets within a two mile radius. Forget about traffic laws, traffic flows or traffic signals. In Kampala, every single car, boda-boda, minivan and pedestrian is left to fend its way through the red mud in a daily battle of petrol fumes and dust. It is dauntingly beautiful to see.

I decide to treat myself to a moto-taxi ride instead of walking to the hostel some two neighbourhoods behind the hills.

‘No need of roller coasters in Uganda. Take a “boda” in rush hour in Kampala and you’ll have enough thrills for a year. We wind up and down wide avenues with inexistent traffic signs, dodging minivans and fiddling in between lanes of idle buses like threading the bike through a needle. I hold on tight and clear the sweat of my face while I see how people acknowledge me with a shy ” How are you?”, “How is your day going?” whenever we dare to stop. I finally arrive into the hostel set in a beautiful colonial house under thick tropical trees and finally rest my tensed body on a lounger for a couple of minutes.’

Two Norwegian sisters join me in chitchat at the lobby. Volunteers for months, they explain how Kampala is safe and how laws are strict for petty crime. ‘If someone is caught stealing, he gets beaten out naked and if the police doesn’t arrive at the right time, he can even be beaten to death’ , she says, as she writes down on her Moleskine. Reassured, I walk past the gate and into the west hills of the city for a taste of the capital.

As I head to the National Mosque, the well-known Ugandan friendliness fills the afternoon air with greetings. I chat to two locals girls as I fasten my pace and offer them cookies, which they delicate place on a tissue ‘for later’, before explaining that a woman eating in public is frowned upon in the city.

In golden details, the plaque at the Arabesque-style building proudly reads a peculiar name: ‘Col. Muahmar Gadaffi Mosque’. An Ugandan comrade, Gadaffi’s petro-dollars financed and oversaw the construction of the second largest mosque in Africa -after Casablanca’s- on Idi Ami’s Uganda, back in the seventies.

A pink arch dominates the entrance and opens up to a porch of intricately detailed lamps. The main hall is empty and carpeted by Saudi’s best, while the tinted windows, extravagant in these latitudes, came from Sudan and Morocco. I am asked if I want to climb to the top of the minaret and I excitedly say yes. The spiral staircase winds up a narrow and dusty tower that rises towards a blue sky that dominates a horizon of green hills and slums that extend from the city centre all the way to Entebbe, Lake Victoria’s retreat.

I buy groceries and with the help of a mototaxi, I cruise along the standstill traffic of rush hour and back to the hostel. With no hot showers and frequent power outages, the night feels as rogue as the Kampala of four decades ago.

I pour myself a cup of coffee at the sound of heavy downpours and distant thunder, the morning air cool and virgin like the hills behind the city.

In town, I sort a bus ticket out of Uganda with Kampala Coach and buy a chapatti carefully rolled under a sheet of newspaper.

At the Old Taxi Park, hundreds of people try to sell all sorts of goods through the crammed minivan window. Flashlights, disposable radios, cakes, loafs of bread. I buy a bottle of Coke and sip as we leave the cramped carpark with millimetric precision and by the Masaka Road, the smell of charred meat and maize mixes up with the smell of fresh fish and sweet fresh fruit.

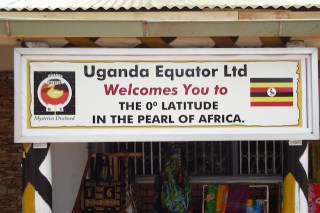

An hour later, I reach The Equator Line. A dated concrete circle representing the passing of the infamous line over Ugandan territory. In big letters, ‘UGANDA EQUATOR’ proudly display a black line that divides the country and the world, into two large hemispheres.

I take some photos and three young local girls smile and snap pictures with the mzungu on their fancy iPhones. A local guide explains the Coriolis effect on some yellow-painted dishes and a group of Indian tourists tip him in awe.

On the return trip, I get off at Buganda and walk to Mengo Palace.

‘I had seen references to Mengo Palace on ‘The Last king of Scotland’. A place of beauty and evil right in the middle of Kampala. The palace sits behind gates that were once gilded and open to the top of a round hill overlooking the city.

My proudly BBC-featured tour guide, elaborates on the happenings of both Obote and Idi Amin within its walls. Obote responsible for the killing of thousands of people in organised massacres and genocides, Idi Amin remembered for widespread violence in an almost cartoonist impulsive behaviour, a character considered comical by the international diplomatic world.’

A dilapidated Rolls-Royce talks of Idi Amin’s takeover from Obote, who was forced to exile in England, and a group of red mud huts talk about Ugandan daily struggles. A local family comes out and ask for their picture to be taken, for it is one of the few times in their lives they see their own image on the screen of a digital camera.

The torture chambers hide behind banana and pineapple plantations. They hide a shameful history of genocide and overcrowding, of starvation and death. Of prisoners that were fed to crocodiles, and prisoners that survived the hunger only to throw themselves at the electrified pit.

Roaches slither through the damp walls oblivious to the palms stamped with excrement and mud, oblivious to the cries for help written in black chalk moments before succumbing to death.

I tip and thank my guide as he explains the country is learning from its past and moving forward, to a Uganda of progress, culture and peace. I nod and close the rusty gate behind me, slowing my pace on the long avenue that extends across a neighbourhood of lush green and simple life.

Back in the colonial house, I pack my bag and sip on coffee and volunteering stories. I vouch to return to Uganda one day and do charity work for a country that worked its way towards my heart.

The traffic lights dance after the heavy shower and the moto taxi swerves across clouds of dust and diesel. The bus is delayed and eight passengers and I wait at a dusty lounge surrounded by the desolation of the market at night. A battered bus crawls over the footpaths and opens compartments for bags to fill out and for seats to be occupied. I leave Kampala late at night, grumpy and tired, once again the road turning dark, turbulent and bone-crushing under the cold high altitude night.

At Gatuna six hours later, I am stamped good bye, and the thick morning fog rests under the silhouette of a thousand hills, of Rwanda.