I rush through a long and bright corridor which abruptly ends on a massive immigration and customs room packed with a sea of travellers slowly moving through the long queues and counters. Queues defining a constant in the social situation of this Caribbean hideaway.

A tanned stunning young lady wears a military jacket. She firmly asks me a couple of questions before stamping my passport and, with a wide smile says ‘Welcome to Venezuela, enjoy your stay!’.

Hated by half of the population as a tyrant and loved by the the rest as a saviour, Hugo Chavez’s Venezuela has seen in a decade, an overinflation of nearly fifteen hundred per cent, a rise in poverty and crime levels and over two million citizens emigrating to Colombia, Peru or Spain.

Indeed, I am briefed by my hostess that slums are a no-go for non-residents and venturing up the hills is nearly a life sentence.

In the early morning, we depart the cold mountains of San Antonio de los Altos with the first rays of sunshine, head downhill through a sleepy Caracas and into La Guaira in the Vargas State.

The navy blue Caribbean Sea roars as the water crashes against thick rock walls placed here after the famous Vargas Disaster of 1999 in which thousands of people died in a matter of minutes when the tall mountains of El Avila collapsed and brought massive mudslides with it.

We reach La Pantaleta Beach -the Panties Beach- early enough to find it empty albeit already warm with the wintry sun.

Within an hour, the popular hideaway fills with tanned locals driving sport cars, playing loud reggaeton music and starting a drinking-and-eating frenzy of beer and seafood chowder at mere ten meters from the shore.

Girls wear tiny bikinis exposing their perfectly shaped bodies and heavily worked tan as a testimony of a society well-known for keeping up with a high standard of physical appearances. A picture worth of an advert, ‘por que en Venezuela, Si Hay!’

Three hours later and with my pale skin acquiring a dramatic prawn red tone, we decide to go back to the capital by taking two local buses into the Gato Negro metro station, from which we take one of the cheapest metros in the world – at twenty cents of an Euro for a ride- to Los Cortijos, a middle-class hideaway in Eastern Caracas.

Homemade burgers, soft drinks and chocolate cake are as plentiful as the answers my hostess’ extended family are happy to answer for me. Through this little Venezuelan middle-class window, I notice how everyone seems to be aware of politics and social issues, but most importantly, how everyone seems to be hopeful for better days for the country. I feel as I have made friends for life in a matter of minutes.

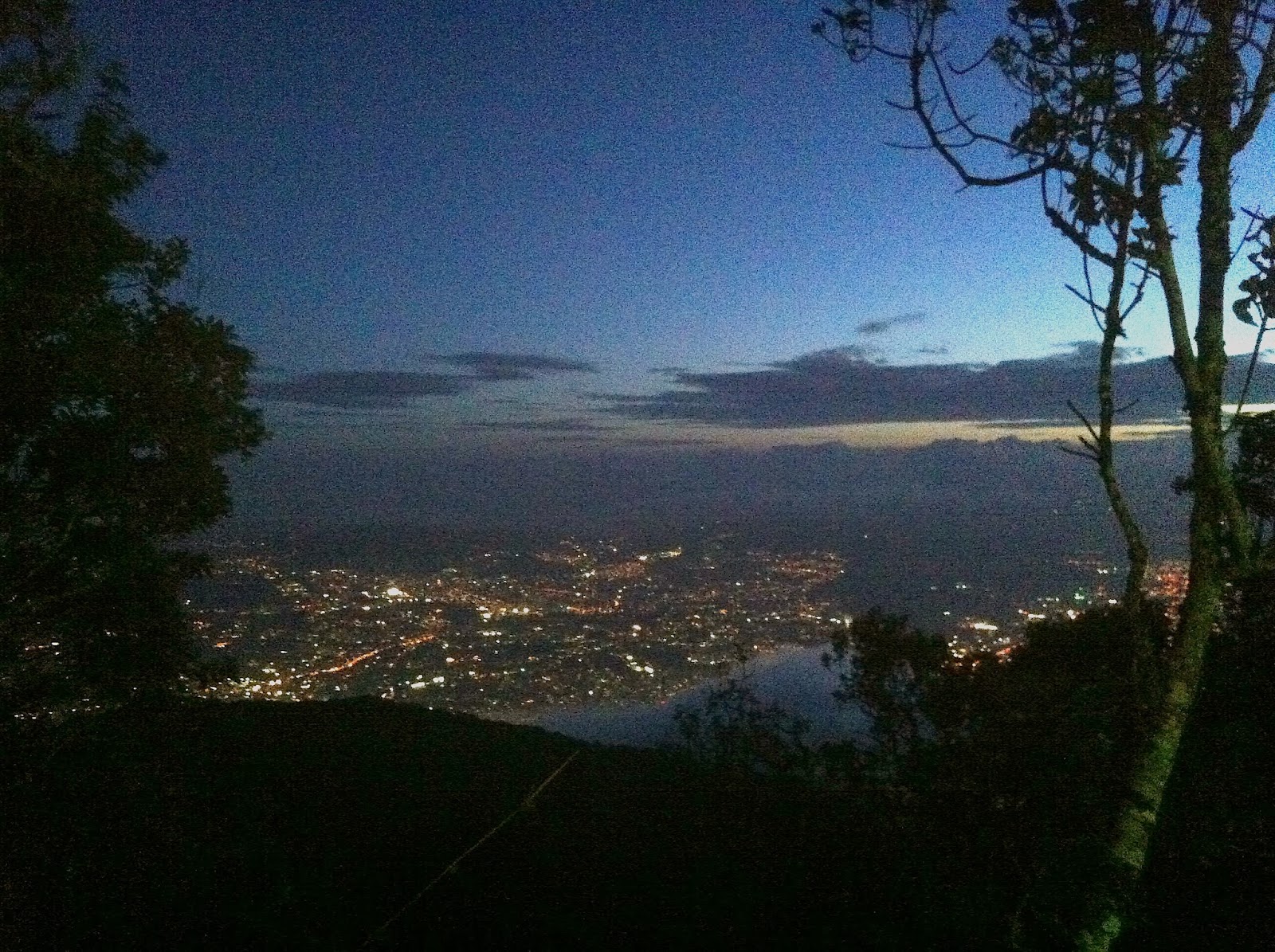

The dark night discreetly disguises the poverty pockets which cover the rims of the narrow valley. As we drive to Caricuao, one of Venezuela’s most dangerous neighbourhoods, in order to give a family member a lift, a wild array of street lights bolt towards the mountain like fireflies in the wind.

I laden myself in body lotion and my skin turns into shades of purple. I uncomfortably sleep overnight, and the next morning, I see the real Caracas.

The Caracas of the traffic jams that can last for hours at the Pan-American Highway, and the Caracas of ridiculous wealth at Chacao. At Altamira Square and for one of the few times in Venezuela, I see fully-stocked supermarkets of blue-fin Madeira tuna and exquisite bottles of Dom. I see briefcases and suits gallivanting with no safety worries and I see private bodyguards waving at the stern Guarda Boliviariana.

During my two business meetings, I am explained that a very small percentage of the population holds an astronomical amount of money. They spend weekends in Miami and go for shopping trips in Paris. They belong the pro-Government elite, they own the country.

When returning to San Antonio de los Altos, I am driven through Los Proceres at sunset, a long avenue where late Hugo Chavez and its government constantly organise military parades. On the TV, a local baseball match is being played, Venezuela the only country in South America where such sport is popular. We eat cachapas for dinner and late at night, when the hills are quiet, I step outside the balcony and look over dozens of little villages that seem to light candles of prayer to the dark sky.

‘My last day in Venezuela becomes a mixture of emotions and landscapes. From the early morning visit to the stables and riding school in the Valley near Los Teques, to a typical ‘pabellon criollo’ lunch with my new Venezuelan family, and finally, to a rather melancholic drive to the airport strongly guarded by advertising outdoor signs featuring the late Hugo Chavez’s stare.’

Air France flight three-eight-five is called as I finish my last arepa of the trip and hug my hostess goodbye. For boarding, we are called in groups of twenty into an airbridge of pure intimatidation.

– ‘Good Evening people, hand luggage in front of you please’.

– ‘Now step back!’

A sniffing dog loudly pants and searches for any traces of drugs or explosives on our hand luggage. He stops by the person standing next to me and my fellow passenger is immediately grabbed by the arm and taken away to a little room. My heart races in unjustified guilt as the dog passes by and our little group is cleared for a second security check in which our bags are opened and our bodies tapped next to the airplane door.

Once finally inside the aircraft, I look out the window for a terminal being pushed away from us, and with it, the problems of a socially destroyed country. For ten hours I watch a movie and sleep, only waking up as breakfast is served over Lisbon and landing is announced next.

At Charles de Gaulle, I take the opportunity of a quick transfer to check my semester grades and with a smile, I board my flight to Dublin.

The visit to Venezuela will always be memorable. It remains as one of the biggest contradictions I have ever seen. A place of bountiful nature, gorgeous beaches and beautiful people. The qualities of a paradise now submersed in misery, violence and poverty.

It is through the eyes of a middle-class family that I have experienced it, I have lived it, and I have now hoped for better days.