I hear a knock on my door and swiftly leave the dark dorm room, joining a fellow backpacker from Austria in a waiting taxi. We have teamed up for the next leg of this trip and, despite being early morning, numerous market stalls slowly congest the streets around the hostel.

As the white Toyota cruises towards the main coach station, which lies away from the city in a field behind the airport runway, the early morning scene of the city surrounds us. Here, groups of locals gather around government-funded fitness instructors, performing squats and jumping in sync around Inya Lake, a green oasis in the middle of a spotless neighborhood, cleaned by government staff wearing creme colored uniforms and sweeping the street with palm leaves. A privileged area dotted with foreign embassies, luxurious houses and luscious gardens.

Almost half an hour later, we reach the busy bus depot and board our coach. It is brand new, Chinese manufactured and the air conditioning is blowing at full power.

North of Yangon, the coach takes a wide dual carriageway linking the largest city in Burma with its counterpart Mandalay. Despite the obvious large investment made to build it, the road seems to be empty and only a few buses and trucks are seeing travelling around.

First service in the morning, means plenty of seats are available and, as foreigners, we are given the seats in the first row, so we fully enjoy the loud Euro-Burmese pop music videos coming out of the small flat-screen television and experience first hand stomach-wrenching turns whilst the bus speeds through windy roads, small villages floating in vast rice fields and conquer bridges spanning over wide muddy rivers. I soon discover why we were handed over a black plastic bag when we boarded the bus. Burmese people can get carsick. A lot.

Three hours later, we arrive into the mile-long village of Kyaikto and proceed to walk, through red dusty streets, to a small hotel in which basic rooms are offered.

Ever wonder where six US dollars can take you in Myanmar?. Apparently it is enough for a space with twin beds placed in between dirty walls covered in reddish clay under a noisy ceiling fan. A semi-open air bathroom and cold shower complete the set of amenities, although Wi-Fi adds a toucgh of modernity to it, so the few French foreigners around me are seen in the wide open common area researching for cycling routes in their iPads.

Basic accommodation aside, the peace of the Burmese countryside is unbelievable. The noise of farm animals in the background, the bells of the distant pagoda and the ceiling fan whirring at maximum speed over my hard bed make for one of the best siestas I have ever had in my entire life.

Once the sun declares a truce, a truck is boarded, an experience shared with some thirty local passengers squeezing in rows of five at the back of a modified Chinese truck. A necessary and somehow exciting ordeal up the vertiginous narrow road which climbs nearly two-thousand meters above sea level to the sacred place of Kyaikhteeyoe, commonly known as The Golden Rock.

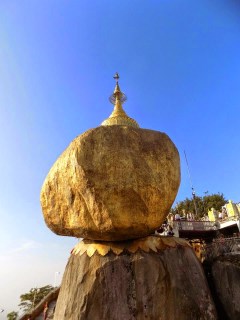

Magically balanced at the edge of a steep cliff, the Golden Rock is the third most sacred place in Myanmar.

The legend says that the rock itself rests over a strand of Buddha’s hair in a mountain range that limits the fertile lands of the Sittoung River delta on the South and the greenery of the cold hills that extend their way North to the Himalayas in the Chinese border. A place beautiful enough to turn anyone into Buddhism, legend states.

With the full moon festivities approaching, pilgrims from all over the country flock into this sacred place and are allowed to spend the night in the mountain. A proof of pure faith, I spot entire families extending bed sheets and soft pillows across the fresh white tiles, kneeling on the floor and sharing small pots of food.

Women close their eyes and, almost in a state of deep and pure trance, loudly pray and bow in front of the rock, crowned by a small shiny pagoda, whilst only the men are allowed to get closer and stick thin leaves of gold to the solid acrobatic boulder.

Only a few steps downhill, a market built just like it was hanging by the hill, colorfully sells food, cheap plastic toys, souvenirs and even livestock, turning dark and Dantesque-like at times when passing through traditional Chinese medicine stalls selling a ‘magical’ elixir based in a mix of formaldehyde run through a sticky amalgamation of animal bones, goat skulls and snake carcasses.

A trip to Kyaikto could not be complete without witnessing the sun setting over the plain lands, reflecting in the waters of the distant delta, scenically coating every little spot of landscape in a symphony of golden and orange colors.

It is also the time for foreigners to compulsory return down the zig-zagging road into town, where dinner is shared with three other fellow backpackers met whilst being tossed about at the back of the truck around the dark hills.

After sharing a meal, I am the last person awake in the hotel. The two receptionists around me have fallen asleep over red worn out deck chairs, listening to the Burmese news on the neglected radio system, lulled by the background sound of chirping crickets and palm trees swinging with the midnight breeze.

Early and swiftly, I leave the most tedious travel companion I’ve had and walk down the road, starting a previously planned long return journey to the big city.

Despite being sold a ‘VIP direct service’, I am told to board an old and dusty coach, departing almost twenty minutes delayed.

Having bypassed the perks of public transport in Myanmar on my journey into the Golden Rock, I can instantly predict an authentic experience to be had within the next hours.

Maneuvering for a few minutes to avoid colliding with some street vendors, the bus slightly skids in the red mud and pulls out of the garage, seconds before we are invaded by pilgrims who run towards the coach from the ‘truck station’, having just descended from the mountain after a warm night praying.

Every seat is filled up in seconds, clearly representing a challenge to the driver and the bus’ suspension which seems to have seen better days in the past.

I move to a seat in the last row and open the large window. Morning breeze fully blowing in my face, and villages passing by behind each bend. Nobody around me speaks English. I sit silently, contemplating the dynamics of a local bus ride, just like travelling in British Burma.

The bus stops roughly every five minutes and collect passengers which now crowd the aisle, breathing heavily when some sort of extreme G forces are felt due to over-speeding , black plastic bags needed.

Sitting beside me, a man with a colorful Hindu mundu smiles and play with his modern iPhone, chatting to his travel mate who loudly chews betel nuts wrapped in green leaves, concluding the ritual with the ‘spit from the throat’ tradition, politely done into yet another black plastic bag.

To pass time, the driver decides to play a Burmese movie. Crowd immediately fix their attention to the small flat screen television and laugh every time the main overweight character bounces people around with his large gut. Apparently he’s a rapper living in Yangon, but he owns a tractor and a Hummer?.

Three hours after leaving sleepy Kyaikto and eighty-five miles down the road, my stop is called and I squeeze my way through the crowded bus.

The heat is nearly overbearing and I am offered a cheap taxi lift by a local. A confusing situation, once we agree on the fare, he runs away without saying a word, bringing an old bike with a tag-on seat on the side a few seconds later.

He grasps a few English words and tells me to seat and hold tight, ploddingly pedaling through the dusty streets of Bago.

Bago, (formerly known as Pegu) is one of Myanmar’s largest towns and gets its name from the Portuguese who created a settlement in the area, which became an important crossroads when the Yangon-Mandalay train line was built.

My driver pants loudly and sink his legs in the pedals whilst we cram through the busy street market, avoiding incoming traffic in tachycardia-deserving turns.

Once in the train station, queues of local passengers purchasing tickets are formed, however, an officer walks me into an old office lit by a noisy neon light covered in cobwebs and dust.

He pulls out a plastic chair and kindly offers to grab my backpack and a bottle of water. He then sells me a handwritten paper ticket.

A brand-new blue sign in their office states both in Burmese and English: ‘Warmly welcome and take care of the tourists’ , which seems to be some sort of a motto in a country that has recently woken up from its domestic lethargy.

Train ticket in hands and battling the scorching heat reflecting on the village tin roofs, streets dotted with pagodas of all sizes and temples are discovered, though my main goal is to reach the impressive reclining Buddha, one of the few crafted in detail and colors in Southeast Asia.

Despite resting in a rather simple setting, at nearly the size of an olympic pool resting in a bed of black tiles, the Buddha is an intimidating sight, resembling a giant waiting to be fed in the middle of the Burmese countryside.

‘Come on in, we have Wi-Fi’ is announced by a shy restaurant owner in the main road. In the end, a pause from the heat is badly needed and energies are replenished with a plate of fried rice and a large bottle of water, excellent option to shelter and pass time before heading to the train station, capturing the moment of pure countryside quietness before the 15:35 train from Mandalay noisily arrives into the platform.

And what a train ride. First class carriages are covered in a lacquered brown finishing, with green ceiling fans and seats separated by an enormous old-fashioned leg room.

My seat partner plays Candy Crush in her awfully large mobile and, at the sound of basic English words coming from her wide white smile, she offers me fresh fruit and food, vocalizing the words ‘fresh’, ‘eat’, ‘very good’ repeatedly.

The train ride to Yangon takes about an hour and a half, loudly skipping over bent rail lines surrounded by light green rice fields and golden pagodas distantly crowning the hazy horizon.

My last hours in Yangon are spent in the hectic grid-like streets of the city center, through the timeless red-bricked Secretariat building and a late afternoon pause in the Independence Monument, where tourists and a few foreigners alike closely watch the dynamics of the water fountain projecting in front of the spotless white City Hall.

A badly-needed shower and my first typically Burmese dinner follow, whilst the rest of the evening is unexpectedly spent learning about the peculiarities of this country from the eyes of an English expat I meet at the hostel.

Quenched by numerous bottles of Myanmar lager, I soon learn that mobiles were introduced into the country two years ago by a Qatari company and that Coca-Cola shares almost the same timeline, annihilating any other soft drink brand in the country with their aggressive marketing campaigns.

Expats are given 60-day visas only, forcing constant trips to nearby Bangkok in order to re-entry the Union, an unpractical yet sharp way of recycling or getting rid of unwanted foreigners.

I briefly sleep before spending my last kyats in a taxi to the airport, once again ending my time in this special place through the leafy avenues of the Northern neighborhoods just before sunrise.

Airport formalities are cleared in a record time of five minutes and I proceed to board my Air Asia red plane along with fellow tourists and a group of Burmese laborers waving their red passports around.

The engines roar and the plane steeply soars over rice fields before making a sharp turn South, conveniently flying over the streets, lives and stories of the busy morning in Yangon, former capital of a country that has just discovered Western life, without giving up the authenticity of its traditions and the warmth of their smiles with every genuine gesture of kindness given. At least for now.