It is midday and the heat below sea level immerse both temperature and mood into a sultry limbo. An immigration officer stamps a paper stub on departure from Israel, leaving no trace of ever visiting the place that now lays behind the security fence and an improvised duty free shop. A short bus journey assist in crossing the river over the River Jordan to equally heat stricken tourists and ceremoniously marks my entry into the Kingdom awarded by the British ruling to the Hashemite family East of the muddy Jordan River banks.

The heat at this time of the day is overpowering and the fact that we are standing in terrain below sea level increases the temperature like a giant concave mirror. A Chinese couple and I hail a taxi all the way to Amman, some forty miles up the mountains.

Rows of trees from the nearby date farms break through the streets of small villages dotted with dusty houses, the distant dry mountains rising up on both sides of the valley like rims of a broken terracotta vase.

I engage into conversation with my Chinese travel companions and I am told stories of childhood under the controversial one-child-per-family rule. As the Chinese middle class emerges, the opportunities for studying abroad grow as fast as the pressure mounting on success. The girl smiles and in a canned American accent acquired over years lived in San Francisco says:

– ‘Backpacking around the world remains a contradiction to the traditional modus operandi of the Asian society. We are encouraged to finish school, go to university, marry, have children and retirement. We are different and are excited to be doing this now.’

The road dips into a massive bowl-like valley and I see Amman, the real Middle East.

Forget about the immaculate gardens of my time in Doha, or the slave-built skyscrapers showing the glow of petro-money in Dubai. In the Jordanian capital, streets wind up and down hills with no apparent sense. Long and broad boulevards cut through the arid terrain in aggressive line ups of shiny SUVs and ramshackle sedans, sprinting in races directed straight towards the numerous set of lights and roundabouts.

A Friday evening is part of the Arab weekend, the fresh weather of the high mountains instigating families to indulge on cotton candy and plastic toys around the Amphitheatre at Hashemite Square. I nestle myself in a coffee shop and, while the coffee, mint tea and falafel with hummus is served on the table, in a thick accent, the waiter loudly says: ‘Welcome to Jordan my friend’.

I find a cheap hotel and I am assigned a fifth floor single room. I open the window and take a deep breath, taking in the fresh crisp wind now blowing through a valley covered in street lights.

Pitta bread, hummus and labhne for breakfast in the small lobby of emerald-colour padded sofas and melamine tables. I am joined by an American and two Canadians, our wandering minds making on-the-spot plans in a clear thirst to see as much of the country as possible.

For half a dollar, a bus takes the American and I down the Dead Sea Road, covering the distance between the peaks of the Amman valley and the flatness of the lowest point on Earth in no more than twenty minutes. The driver leaves us at the junction for Al Rama, where it takes us two minutes to hitch a ride down the Dead Sea shores.

I am dropped at the Samarah Mall, from where the Sea looks deep blue, the thin line between sea and sky only broken by the pale brown and white of its shores. Affixed in the core of the lowest point on Earth, no fish or plants live on it, the salinity of its hot water too hostile to sustain any sort of life. I sip on my coffee while I sit in the comfort of the air conditioned cafe and remember:

‘The van circles around the streets of Bahcelievler. It is a sunny and cold morning in Istanbul and a small conversation sparks amongst the cramped seats.

– Where are you guys from? I ask.

– ‘We are from Jordan. It is a beautiful country’. A young couple replies, their broad smiles highlighted by their round brown eyes looking against the tinted windows.

-‘Heard great things about it. I am planning to visit later this year’.

– ‘Add me on Facebook, we will be glad to meet you when you visit’.

The same broad smile greets me from the distance, highlighted by the sunshine reflecting on big designer sunglasses. A big SUV stops next to me and, in the haste of a brief stop next to the busy highway, my hostess introduces me to her two kids, sitting in the backseat eager to open the windows and let the salty air in.

It is a road of unique beauty down the shores of the Dead Sea. Pieces of dark asphalt embedded in cliffs of red rock that emerge from below sea level like a giant octopus reaching for the blue sky, the air entering through the windows enchantingly refreshing. I am driven to the nearby Wadi Mujib National Reserve, whilst I am told to prepare to be soaked.

A narrow canyon has become one of the latest tourist attractions in Jordan. Ropes hang onto giant boulders and aid in climbing over waterfalls of fresh water flowing in the opposite direction. It is a wet combination of adrenaline and physical stamina, my breath surrendering to the bizarreness of the moment and place, and my mind finally forsaking the usual correctness in the same mental state of a five year-old playing with mud.

With no taxis around, I dry myself with an improvised towel and stand next to the road to hitch hike. I meet Hamad. He speaks no English but silently drives me the fifty kilometres of Trans-Jordanian Highway to the Samarah Mall. With all windows fully opened, Hamad heavily smokes and pants. Speed limits seem a mere myth to Hamad and, at one-hundred-and twenty kilometres an hour, the rest of the cars seem to slug behind the broken pavement in dangerous overtakings. Hamad smiles and indulges in the wind entering from the glistening Dead Sea, for this cleanses his lungs from the tar of cigarettes and cleanses his head from sadness.

Starved from the aquatic adventure at the Wadi, I share a barbecue and beer with my local guests, the taste of homemade tahine almost as exquisite as the conversation in the balcony overlooking the Holy Land. The sea beneath us peacefully roars with the late afternoon wind and the swimming pool stands still, immaculately empty at the company of two inflatable pink flamingos left behind. The children curiously flick through the pictures taken from my camera and ask about places far away, about Australia, Ireland, about Greece.

We head down to the shore and I cover myself in the earthy-smelling Dead Sea mud. I float, I pose and float, I read the newspaper and float, the sun seeming to balance its weight over the horizon of flickering street lights pointing to Jerusalem. Indeed, the West Bank might have the beautiful sunrises, but Jordan has the mesmerising sunsets.

I am driven up to Amman by my host and my inquisitive nature, constantly starved for stories to listen, relishes at the memories of a childhood in Jerusalem, silently enquiries to the details of a forced move into the Kingdom of the Hashemites, and finds comfort in the pride of words of successful careers and even larger aspirations for the future.

In the morning, the sun enters through the small hotel window and its weak light clears through the overnight rain. Bold on-the-spot move, I decide to catch a local bus to Aqaba, the luxurious JETT bus not available for a stop in the middle of the road.

The local experience requires patience. It requires waiting a couple of hours for the bus to fill up, it requires lungs of steel to endure the fellow smoking passengers and the hermetic windows and, it also requires a bit of humour.

Over the next hour, I see how the densely populated capital fades into isolated houses sprinkled across the rogue horizon, whilst cars gain momentum over the cracked asphalt of the dual carriageway sloping downwards to the sea. We stop for a bathroom break and a young fella stares at my backpack. He immediately throws his cigarette butt on the floor and taps it with his black moccasin. He introduces himself with a broken English and an awkward smirk.

– ‘Where you coming from my brother? My name is Moussa.’

As the bus rolls down the dry landscape around us, I learn that Moussa is twenty-seven, though he might look a bit older. His brown eyes constantly stare at his smartphone and, cigarette after cigarette, he tells me the story about his blond girlfriend in the United States and the time he managed to travel across the world. An episode of illegal immigration interrupted by a fight with a policeman and a visa overstay.

– ‘I will come back soon. Once the ban is gone. You’ll see. I will marry Victoria’.

Over the remaining three hours of the journey South, Moussa flicks through numerous pictures of Victoria in different poses and his words sometimes slur at the thought of his father-in-law’s Islamophobia, suddenly acquiring a firm and smooth tone at the memory of Jordanian cuisine conquering it.

Life in Aqaba is not necessarily hard, but it will not provide room for any indulgence, trips abroad or even fixing the powerful engine of the now dead BMW. However, I seem to learn a lot from Moussa, for to his eyes, life is simple and fast-moving, the technicalities only to be thought when it is time.

Wadi Rum stop. I desperate inhale on the clean air and walk across the motorway. I hitch two rides into the National Park and at around three in the afternoon, the sun grows orange and the Mars-like landscape around me starts its daily flirting with shades and shapes. I am told to wait at a small hut and I am served coffee with cardamon direct from the bonfire laid on a bed of rocks. Around me, eight men from different ages squat on the dusty floor and timidly smile. A large man in a white beduin robe salutes me and introduces himself as my guide.

It is time to freeze the time. To stop looking at the now signal-less mobile and to surrender to the passing of the minutes, now only shown through the shadows of cliffs constantly changing the landscape around us. The sun hides and the moon becomes our sentinel for the night, its light coating the inert rocks with a smooth tone of silver.

Colourful rugs are laid on the bare sand and, once we dominate the squatting position, fellow visitors and I are served beduin tea around a cozy fire. The night is fresh and a light wind blows through the seven tents here installed for the night. Guttural noises accompany a singing beduin melody and a dinner of chicken and roasted vegetables is finally pulled out of a barbecuer buried in the sand.

Lights go off at 8:30pm and I delight myself with a solo walk around the cliffs, the shooting stars above me drawing white lines through the ethereal sky. The desert surrounds my mind and brings it to a complete stop, encouraging me to wander, to find that inner animal roaming free in the sand, to hear unheard noises, and to face any thought so far bothering its peace.

I go back to my canvas-made hut and sleep immersed in deep silence, in the morning awake before the rest for a sunrise of pure orange beauty in one of the strangest places I have ever slept in.

Once breakfast is served and the last cup of coffee is sipped, promises of visits in Vancouver and Dublin are made. A two-hour bus ride takes me out of the desert, atop the central valley through the King’s Highway and down to the town of Petra, where a fee of sixty US dollars is charged as admission for foreigners.

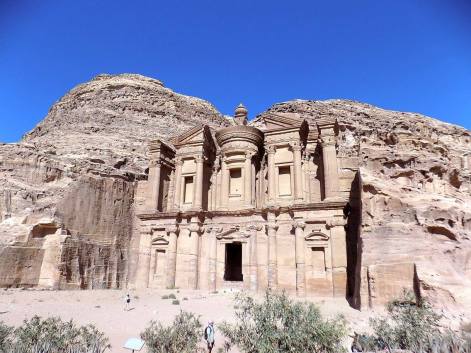

Enigmatic and rustic, Petra always remained as that unattainable bucket list item, as the place that has managed to remain magnificent despite the surge in tourism.

Petra does not disappoint. Round boulders layered in sedimentary terrain have been carved in what once was a vibrant city embedded in the dusty rocks. Up the ‘Indiana Jones Trail’, precarious tea shops hang onto the cliff for the best and most magnificent view of the Treasury, a temple built by the Arab Nabateans in the same period of time as Greek and Roman Empires ruled Continental Europe. Legends claim it once held the treasure of the Egyptian Pharaoh, whilst others claim pirates hid valuable goods in crafted urns.

Further down the extensive site, the remains of an once glorious Roman site seem to dissolve within the rocks, their tall Doric columns at times dramatically protruding towards the cloudless sky. I spot an amphitheatre and, whilst looking at my watch now covered in pale yellow dust and sweat, I climb up the eight hundred and fifty steps to the Monastery, where I sip on an overpriced bottle of water and admire a place as strange as the explanations surrounding it.

There are no hardships on the return journey to Amman, now covering the distance to the capital in the luxurious confines of a JETT bus. At nine in the evening, the traffic-less streets invite for a walk, a mezze and a peppermint tea before bed.

Laundry before breakfast and backpack almost ready for depart. I walk across long leafy boulevards bisected by first, second and third ring roads. Thoroughfares at time too prohibitive for pedestrians, line ups of luxurious hotels where spotless cars await for diplomats, peaceful roundabouts oblivious to the madness of the traffic revolving around them. I meet my local friend for the best mezze I have had in my life at Shams El Balad, where dishes of organic food seem to float over the view of the winding streets, below us looking like the veins of a muscular city beating at the rhythm of the Citadel, proudly standing atop a hill in the distance.

It is a lunch of conversations about lessons learned from the past and aspirations set for the future, before my time in Jordan turns melancholic and lonely. I say goodbye to my friend and wander around the city on my own for the afternoon, climbing up hills and neighbourhoods laid across narrow streets where old neglected cars seem to have been parked for years. Two local girls stare from the table next to mine at the balcony overlooking Hashemite Square and, determination prevailing through the delicate pink veil, one of them extends her arm and offers:

-‘Like shisha? Do you want?’

I push my chair next to their table and spend an hour learning to count to ten in Arabic. The girls smile in between puffs of apple-scented smoke before dropping a single one Dinar bill in the table and leave for home after a day in university.

The next morning I leave a city still plunged into the peace of an autumnal night and, on my way to the modern Queen Alia International, the sunshine once again starts its daily journey across the clear blue sky.

I mentally say goodbye to the country. To the Chinese couple, to Hamad, to Moussa, to the girls that taught me to count in Arabic, and to my local family, promising myself I will be back. As for today, It will be a full flight on this Royal Jordanian Airlines morning commute across the Sinai.